Rusticator Repast

Old Faithful Inn dining room in the early 1900s

From the mid-1800s through the 1920s, it became popular for well-to-do urbanites to vacation in remote locations of extraordinary natural beauty across the U.S. Often dubbed “rusticators,” these tourists sought bucolic settings and opportunities for outdoor recreation, yet preferred comfortable, even luxurious, accommodations to retreat to at the end of the day.

While some establishments, such as the Old Faithful Inn, exhibited classic rustic architecture, many of the destinations were grand Victorian hotels. Nevertheless, this style of vacationing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries led to the popularity of the rustic furnishings that are at the heart of our antiques business, so all manner of historical details related to the original rusticator era are of ongoing interest.

One dimension of elegant adventurers’ vacation experience was the food served in the out-of-the-way locales they visited. Could they expect simple local fare such as venison, beans and flapjacks, or upscale entrees such as Blue Points on Half Shell and Filet de Boeuf Pique aux Champignons?

The answer seems to be the latter, based on our exploration of the New York Public Library’s “What’s on the Menu?” database. Within its treasure trove of digitized restaurant menus from the 1850s thru 2008, we found numerous dinner menus from resorts that were popular during the heyday of country and wilderness vacationing at resorts that had both natural outdoor wonders and the amenities of home.

Here we present menus from five of these resorts, along with period photos of each:

1) Kearsarge House in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, with a menu from 1873

2) Paul Smith’s Hotel in the Adirondacks, with a menu from 1891

3) Poland Spring House in Maine, with a menu from 1891

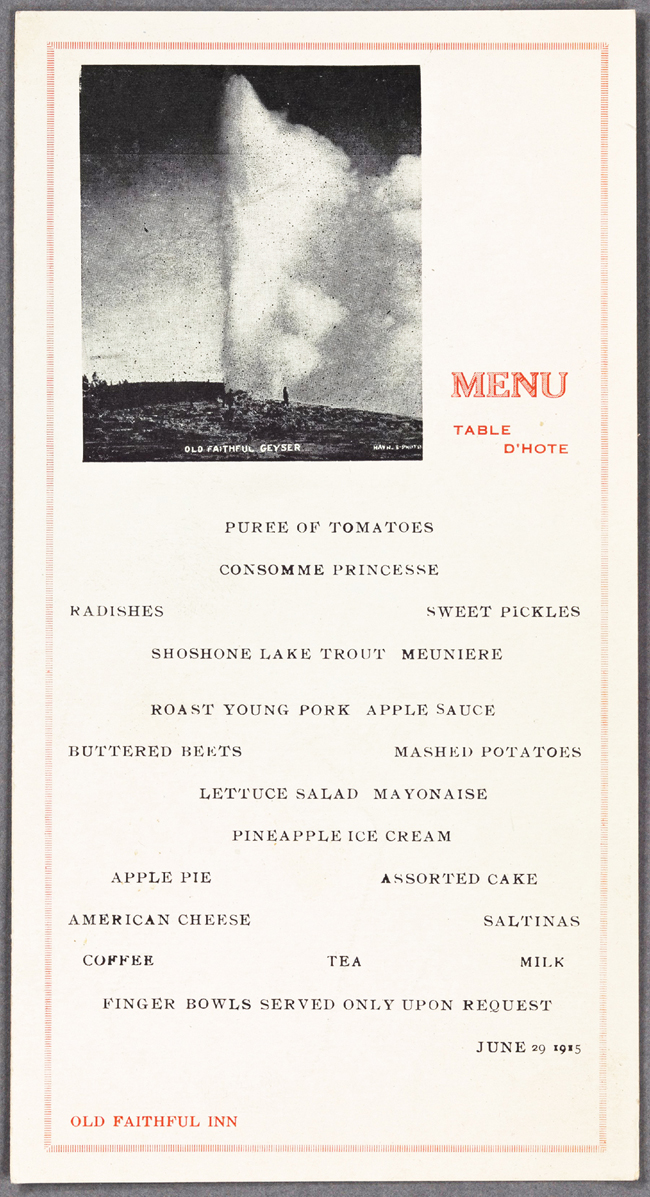

4) Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone National Park, with a menu from 1915, and

5) The Balsams in Dixville Notch, New Hampshire, with a menu from 1917.

It is striking how bountiful the fare was in most of these examples, with a wide variety of meats, fish, relishes, vegetables, pastries and the like. We learned that top chefs in the resort industry prepared meals not unlike what visitors would experience at a fine restaurant back in the city.

Two things made this bounty possible in an era prior to paved highways: railroads and on-site farms. The White Mountains Express, Portland & Ogdensburg Railroad, Maine Central Railway, Adirondack & St. Lawrence Railroad, and Northern Pacific Railroad are some of the early rail lines that would have served these resorts.

The train depot was not far from the Poland Spring House in Maine, but in the White Mountains the station was 60 miles from The Balsams, so everything and everyone disembarking the train made the rest of the journey via stagecoach. This may have inspired The Balsams to establish a huge farming operation on site to produce its own dairy, eggs, poultry, vegetables, livestock, and even trout from its own hatchery. To augment its self-sufficiency, The Balsams also had (and in fact still has) its own power generator and water supply.

The Kearsarge House, also in the White Mountains, had its own farm as well, boasting in its 1887 brochure: “Possessing its own farm of almost 100 acres, the Kearsarge has every day fresh vegetables and fruit. The excellence of its table has always been a source of special pride.” Modern day locavores would approve.

The exception to the more sumptuous resort fare, at least as represented by the sample 1915 menu we found, was at Old Faithful Inn which had a much simpler table d’hote menu presenting a single multi-course meal with few choices. The rail station for Yellowstone was 56 miles away in Gardiner, Montana, so guests and provisions alike were transported from the train depot to the Inn in 4 and 6-horse wagons. Without a large farm on site or nearby, it is no surprise that the menu was somewhat limited in this wilderness outpost.

Stage coach to Old Faithful Inn

The Menus and Hotels

Kearsarge House, North Conway, NH, 1873:

Kearsarge House

Paul Smith’s Hotel, Paul Smith’s, NY, 1891:

Paul Smith's Hotel

Poland Spring House, Poland, Maine, 1891:

Poland Spring House

Old Faithful Inn, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, 1915:

Old Faithful Inn

The Balsams, Dixville Notch, NH, 1917:

The Balsams

A piece of vintage resort china that we acquired after a stay at The Balsams.

A Summer Recipe

In case you would like to recreate a taste enjoyed by rusticators in summers past, here is a recipe from the 1861 publication “Beeton’s Book of Household Management” (found on vintagerecipes.net) for Peach Fritters, which appear both on the Kearsarge House and the Poland Spring House menus.

Variations on peach fritters include donut-like confections of fried dough spiked with chunks of peaches, and flat pancakes dappled with peaches. But in this vintage recipe the peach slices are more prominent than the dough, as slices are dipped in a thin batter and fried, with results much like tempura. Enjoy!

Peach Fritters (circa 1861)

Ingredients for the batter:

1/2 pound of flour

1/2 ounce of butter

1/2 saltspoonful of salt

2 eggs

milk

peaches

hot lard or clarified dripping

Instructions: Make a nice smooth batter and skin, halve, and stone the peaches, which should be quite ripe; dip them in the batter, and fry the pieces in hot lard or clarified dripping, which should be brought to the boiling-point before the peaches are put in. From 8 to 10 minutes will be required to fry them, and, when done, drain them before the fire, and dish them on a white d'oyley. Strew over plenty of pounded sugar, and serve. Time: From 8 to 10 minutes to fry the fritters, 6 minutes to drain them. Sufficient for 4 or 5 persons. Seasonable in July, August, and September.